“UNI” is a peculiar word. When you read or hear it, it immediately seems familiar, and usually the context gives a clear meaning to the word. However, when it stands for itself, its meaning becomes intangible. Is it an abbreviation for “university,” does it denote monochromaticity, is it the French participle of “unir” (to unite)? Or does it even denote an edible Japanese sea urchin or an Etruscan goddess? In its combination of ostensible familiarity and semantic ambiguity, it fits perfectly with the three artists in this exhibition, whose works take familiar elements from everyday life, be they materials, techniques, or image types, and use them to create objects whose possible radius of meaning becomes increasingly unstable and abysmal the longer one looks at them. Seductive at first glance, flirting with the decorative, they turn out to be insidious in the best sense of the word, tilting images that refuse to make clear sense and instead play their games with the viewer.

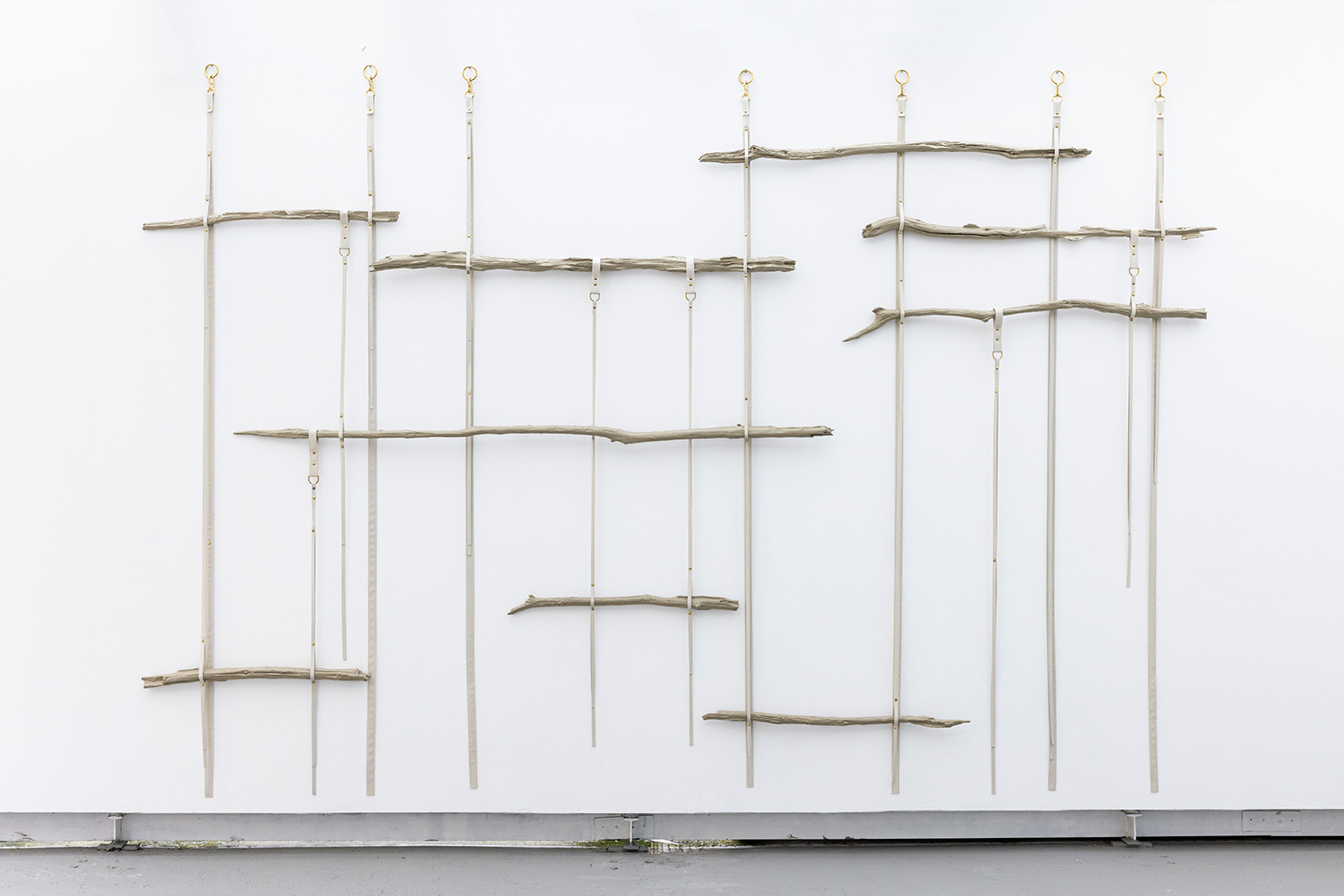

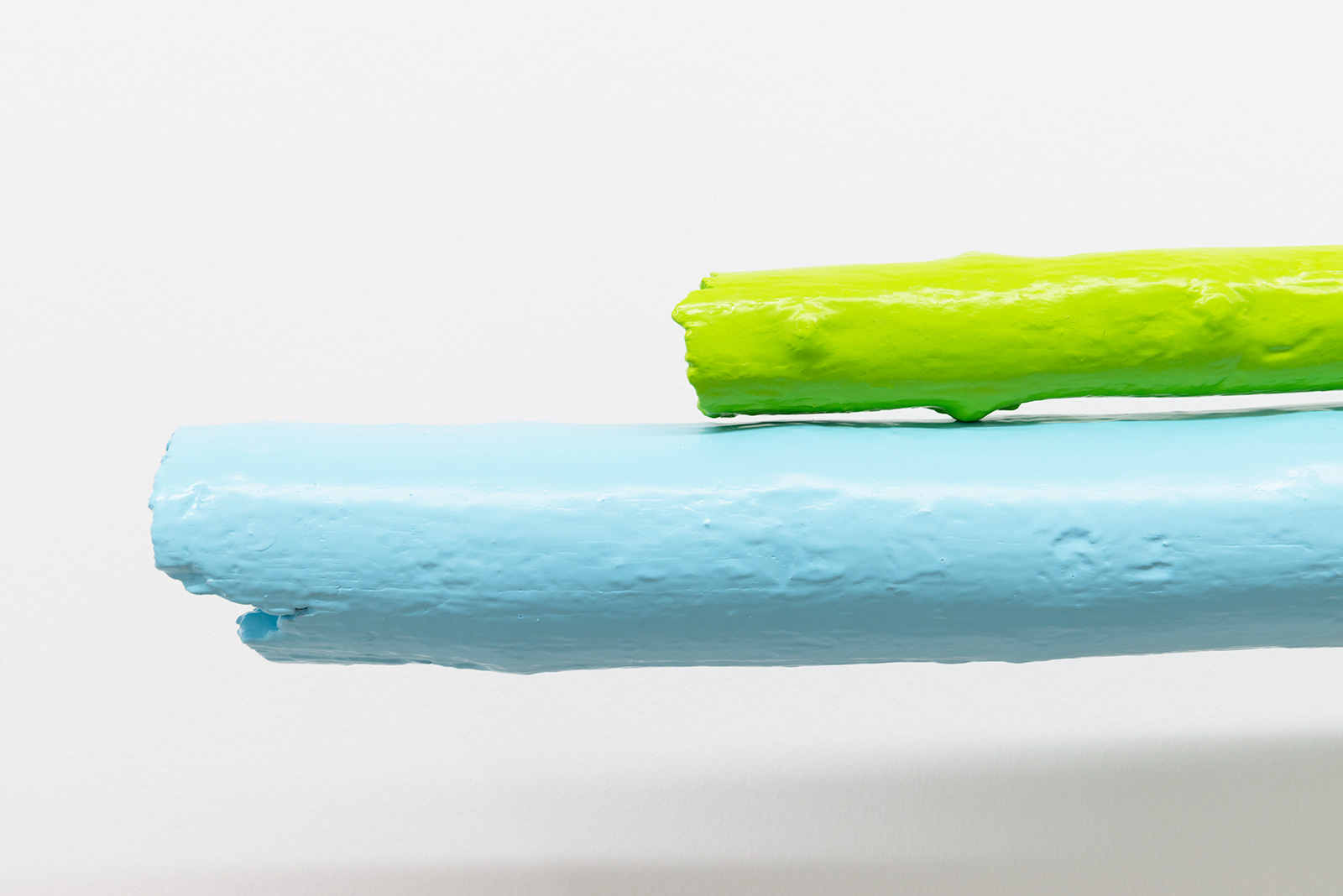

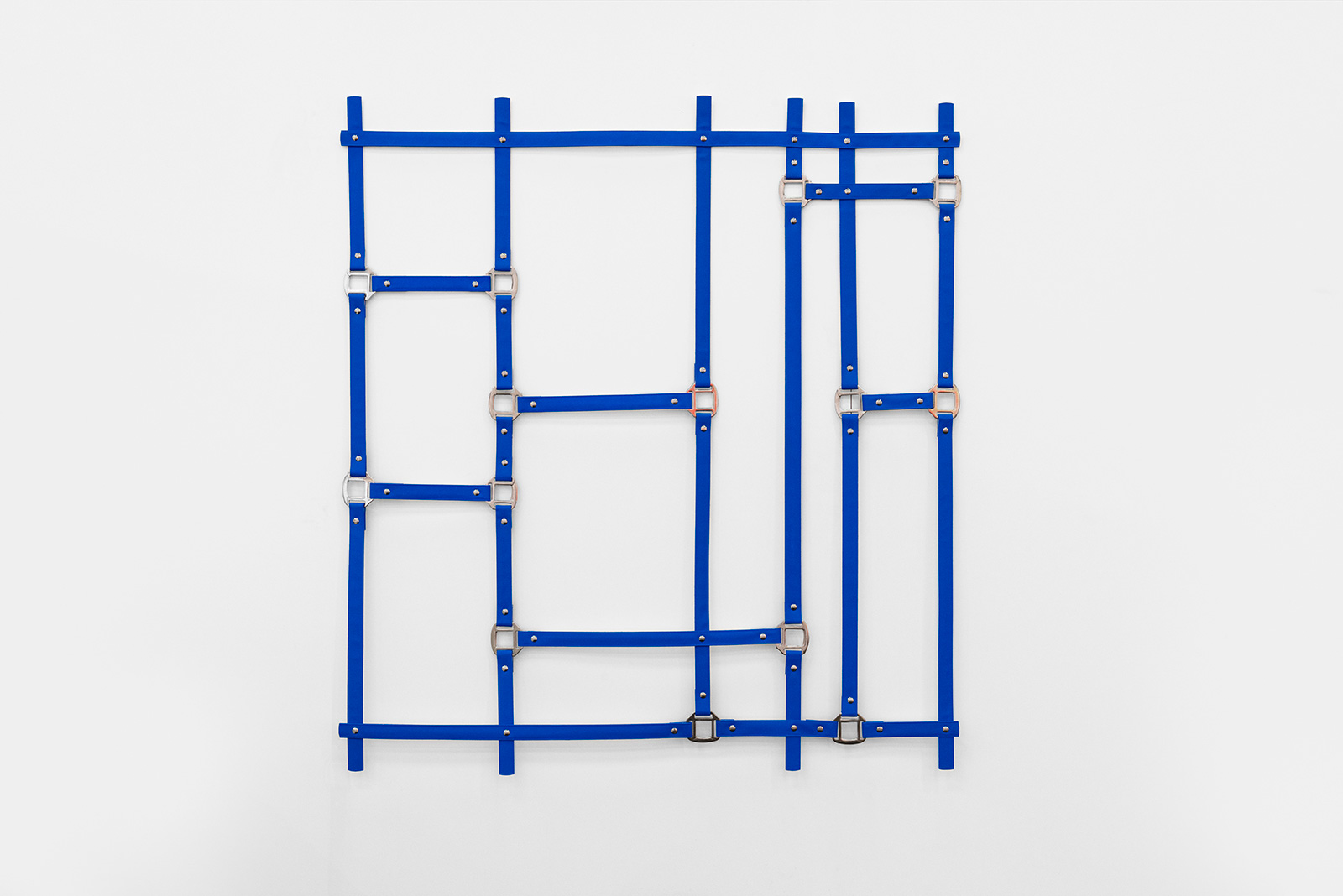

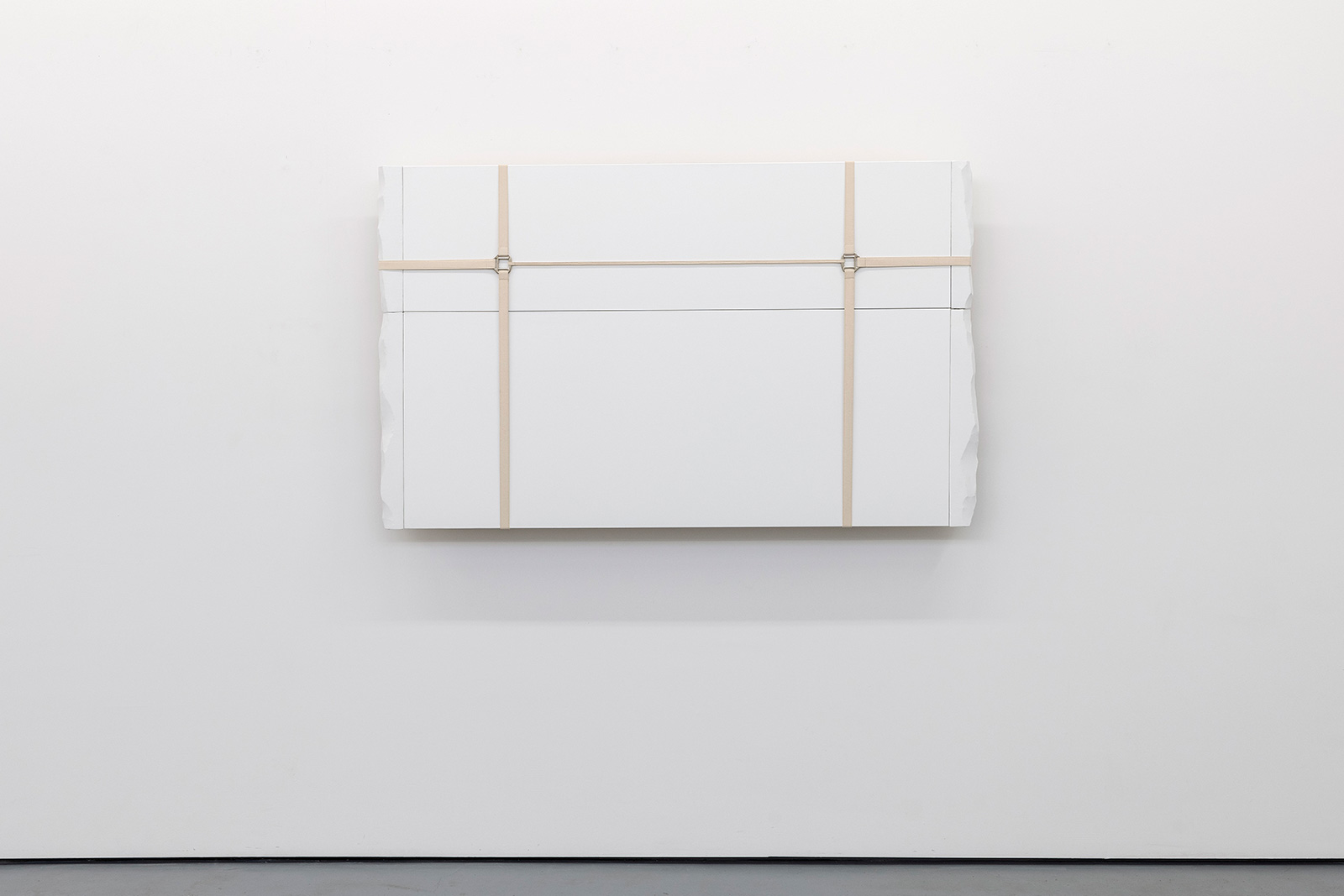

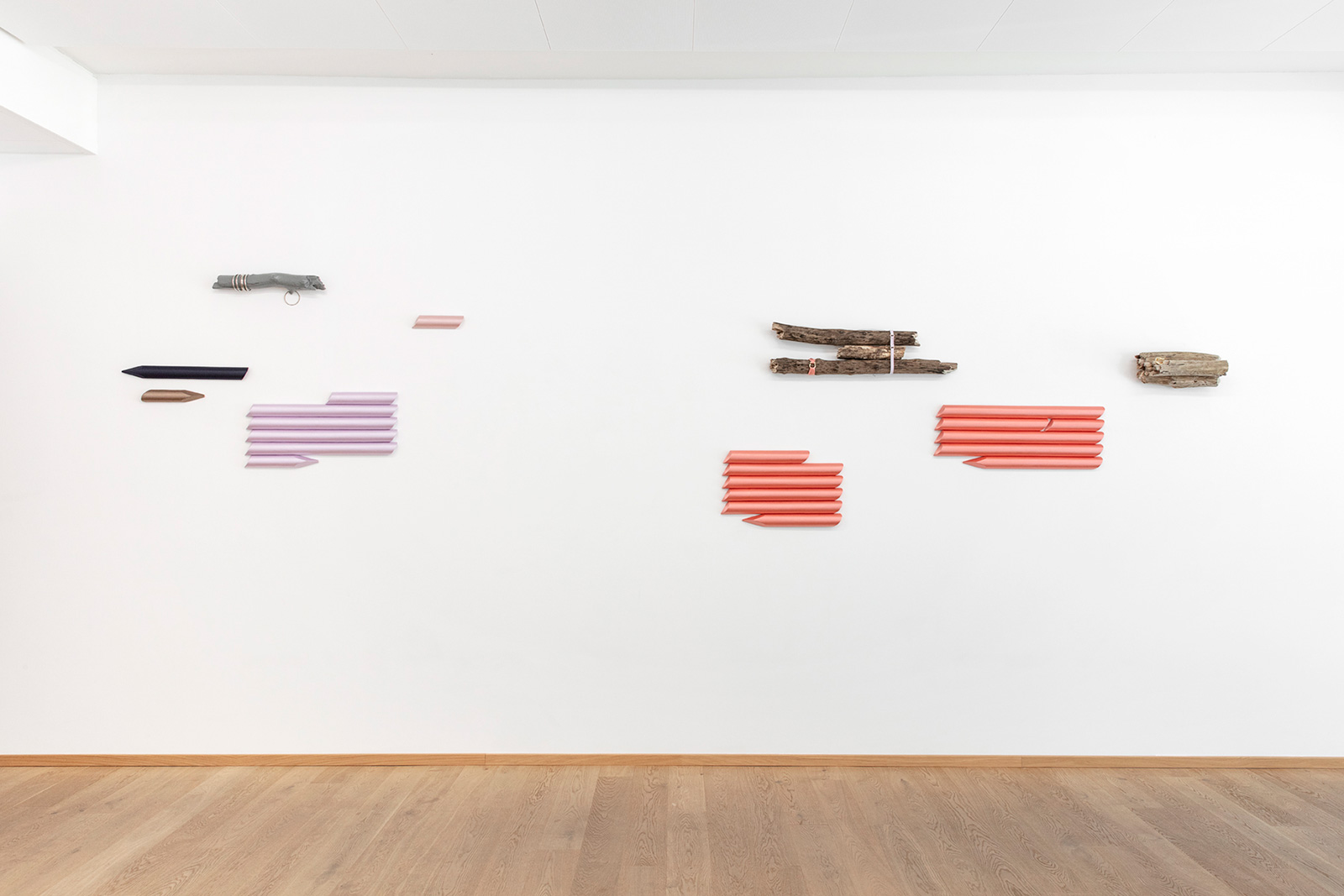

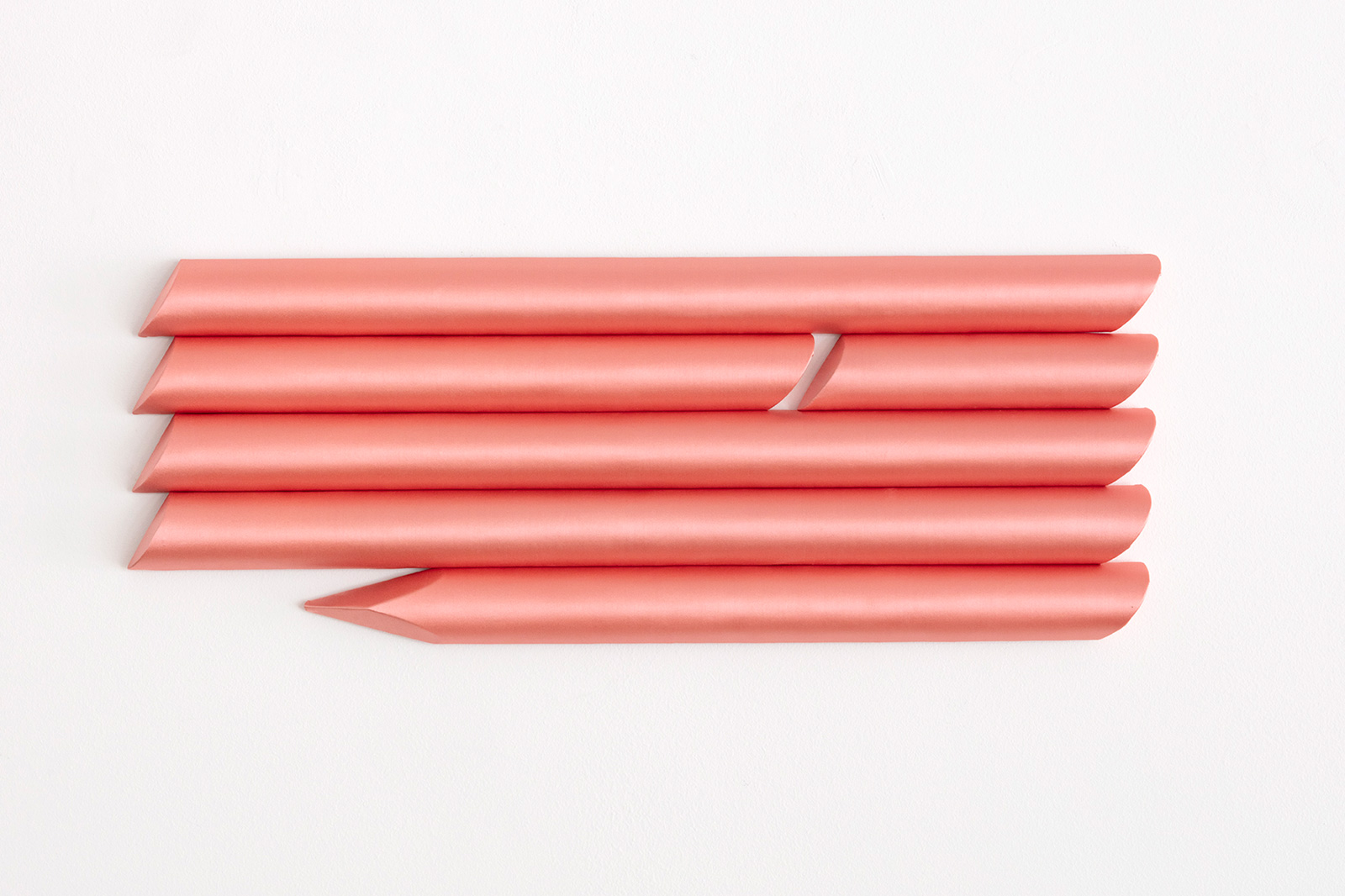

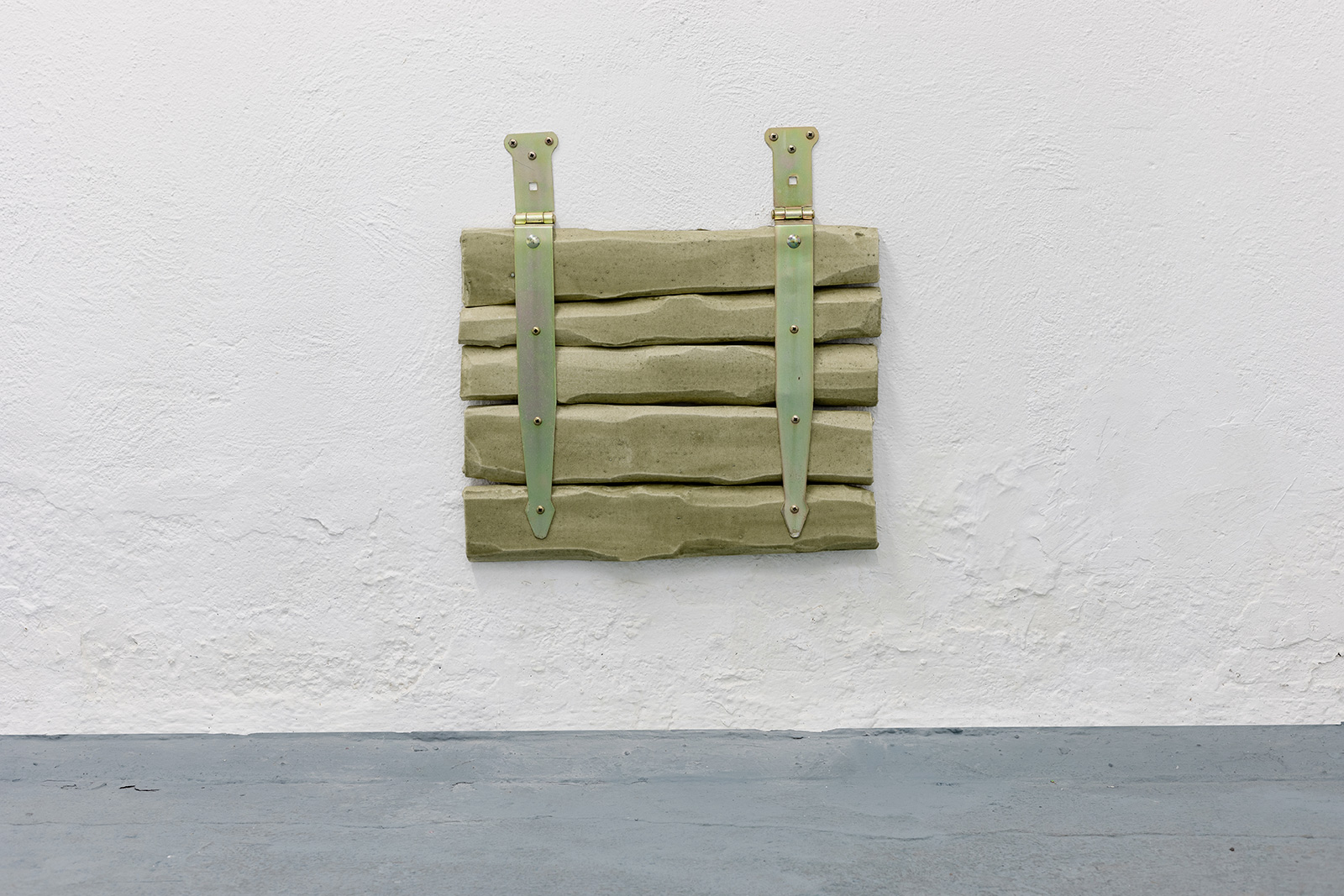

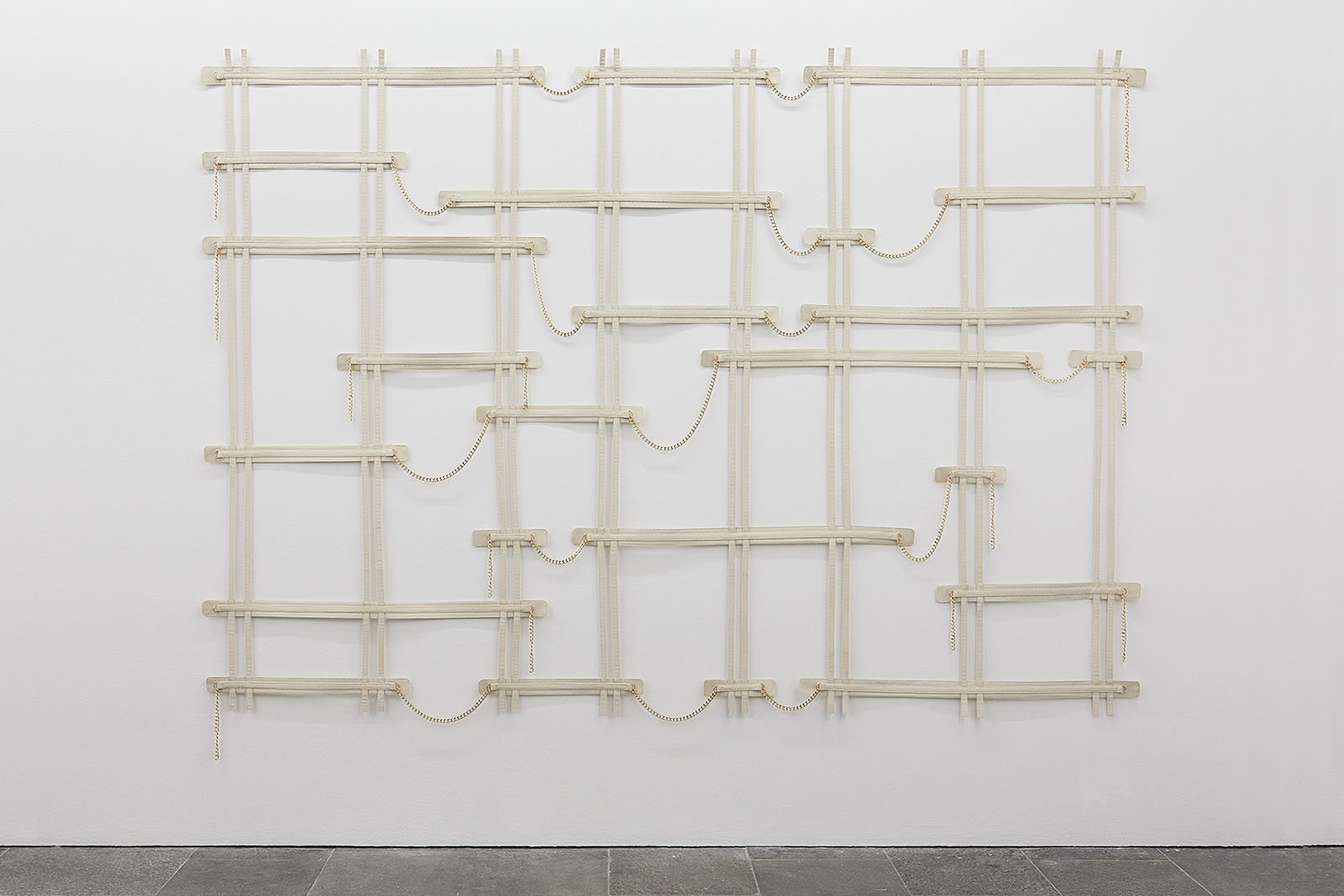

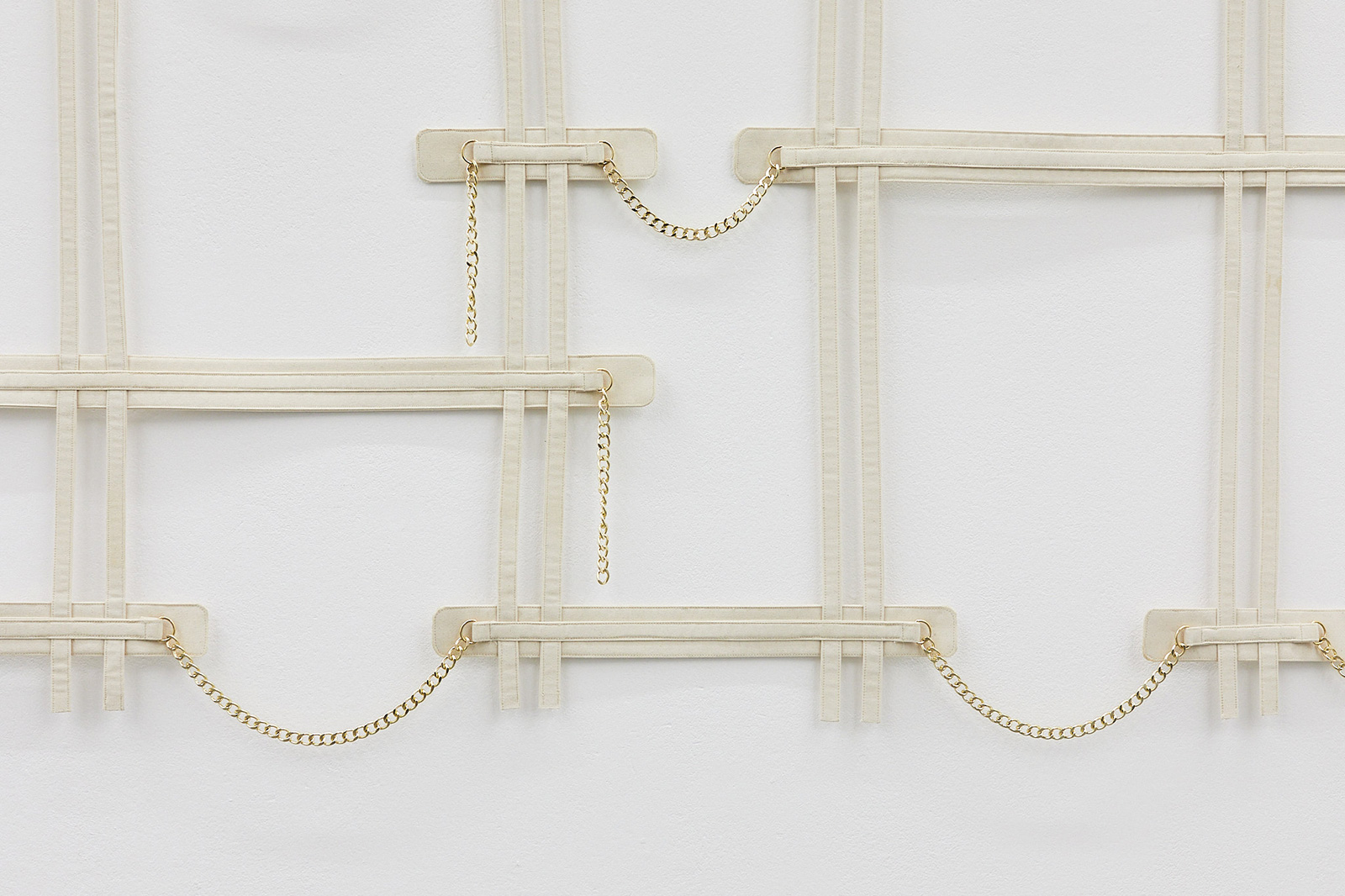

Roman Gysin probes the social charges of materials, the “class struggle of taste,” as he calls it. The lifeworld of socially upper classes is usually characterized by materials with high-quality connotations, processed in accordance with the rules of “good taste.” In less affluent milieus, people must know how to help themselves if they want to create a living environment that appeals to them visually, the impression of a modest abundance that lifts life out of the dreariness. They often resort to imitations, polyester instead of silk, wood laminate instead of veneer. The decoration strategy does not follow “good taste” but longings, just as the imitation is a longing that has become material. There is something rebellious, queer about the imitation, the inauthentic, the semi-authentic, a refusal to accept the normative status quo. The pink lacquered pieces of wood on the floor seem to ironically mock wood as the epitome of dignified naturalness and authenticity. Whether they are “real“ or not is not visible to the eye, but their coloration and surface texture immediately reveal them to be products of the petroleum age; it is natural to read them as fakes. Real wood appears here as imitation wood, we see the imitation of an imitation, a completely paradoxical object. The pieces of wood in the wall installation cannot be pinned down either, they are brought into a geometric structure with straps reminiscent of handbags, illusory nature and illusory luxury intertwine in a constellation reminiscent of Minimal Art and Arte Povera—aesthetics that in certain milieus are considered to be the epitome of “good taste” and which appear here as just another look that can be quoted.

„UNI“ ist ein eigenartiges Wort. Liest oder hört man es, wirkt es sogleich vertraut und meist ergibt sich aus dem Kontext eine eindeutige Bedeutung des Wortes. Steht es jedoch für sich selbst, wird seine Bedeutung ungreifbar. Steht es nun als Kürzel für „Universität“, bezeichnet es Einfarbigkeit, ist es das französische Partizip von „unir“ (vereinen)? Oder bezeichnet es gar einen eßbaren japanischen Seeigel oder eine etruskische Göttin? In seiner Verbindung von vordergründiger Vertrautheit und semantischer Uneindeutigkeit paßt es trefflich zu den drei Künstlern in dieser Ausstellung, deren Arbeiten vertraute, aus dem Alltag bekannte Elemente aufnehmen, seien es nun Materialien, Techniken oder Bildtypen, und sie zur Herstellung von Objekten verwenden, deren möglicher Bedeutungsradius immer unstabiler und abgründiger wird, je länger man sie betrachtet. Auf den ersten Blick verführerisch, mit dem Dekorativen flirtend, entpuppen sie sich als hinterhältig im besten Sinne, Kippbilder, die eindeutigen Sinn verweigern und stattdessen mit dem Betrachter ihre Spiele treiben.

Roman Gysin tastet die sozialen Aufladungen von Materialien ab, den „Klassenkampf des Geschmackes“, wie er es nennt. Die Lebenswelt gesellschaftlich gehobener Schichten zeichnet sich meist durch hochwertig konnotierte Materialien aus, den Regeln des „guten Geschmackes“ folgend verarbeitet. In weniger bemittelten Milieus müssen die Menschen sich zu helfen wissen, wenn sie eine sie visuell ansprechende Lebenswelt gestalten wollen, die Anmutung eines bescheidenen Überflusses, der das Leben aus der Tristesse hebt. Oft greifen sie dabei auf Imitate zurück, Polyester statt Seide, Holzlaminat statt Furnier. Die Dekorationsstrategie folgt nicht „guten Geschmack“, sondern Sehnsüchten, so wie das Imitat eine Material gewordene Sehnsucht ist. Dem Imitat, dem Unechten, Halbechten wohnt etwas aufrührerisches, queeres inne, eine Weigerung, den normativen Status Quo zu akzeptierend. Die rosa lackierten Holzstücke auf dem Boden scheinen ironisch Holz als Inbegriff gediegener Natürlichkeit und Authentizität zu verspotten. Ob sie „echt“ sind oder nicht, ist von Auge nicht zu erkennen, durch ihre Farbigkeit und Oberflächenbeschaffenheit jedoch geben sie sich sogleich als Produkte des Erdölzeitalter zu erkennen, es liegt nahe, sie als Fakes zu lesen. Echtes Holz erscheint hier als Holzimitat, wir sehen das Imitat eines Imitats, ein gänzlich paradoxes Objekt. Auch die Holzstücke in der Wandinstallation lassen sich nicht festmachen, sie werden mit an Handtaschen erinnernden Riemen in ein geometrisches Gefüge gebracht, Scheinnatur und Scheinluxus verschränken sich in einer Konstellation, die an Minimal Art und Arte Povera denken läßt – Ästhetiken, die in gewissen Milieus als Inbegriffe „guten Geschmacks“ gelten und die hier als ein bloßer weiterer Look erscheinen, der zitiert werden kann.

Photo: Kim da Motta